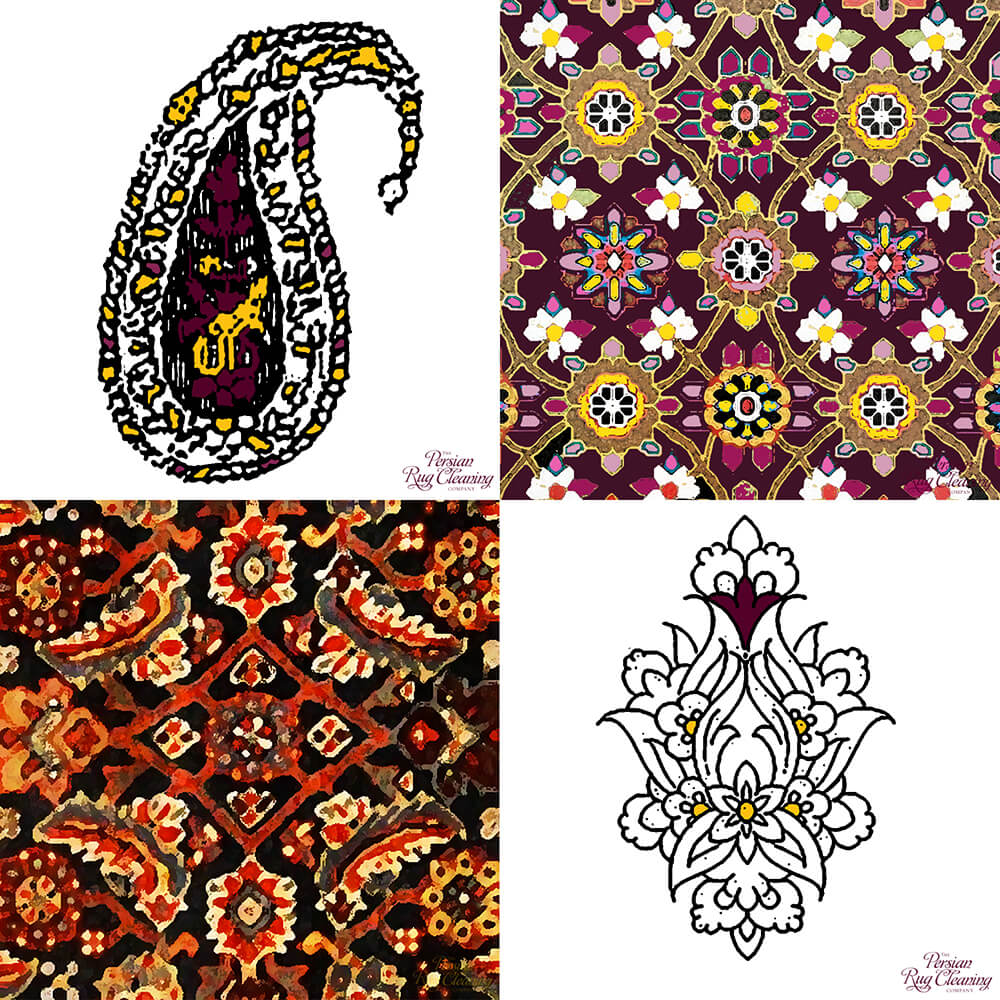

Common Rug Motifs

I find the most interesting aspect of rug design and identification to be the study and appreciation of motifs. Common rug motifs are patterns which are shared by most major rug weaving areas around the world. Although we categorise these motifs into common groups, each region of weavers will have their own way of executing them. They are wonderful to examine because the specific interpretation of a particular motif can give clues as to the region responsible for the weaving. At the same time these clues link it to the creations of other regions. In fact the similarities and differences between a geometric and floral adaptation of the same motif act as pieces of a timeline from which we can observe the evolution of designs, and the migrations and influences of weaving groups on one another.

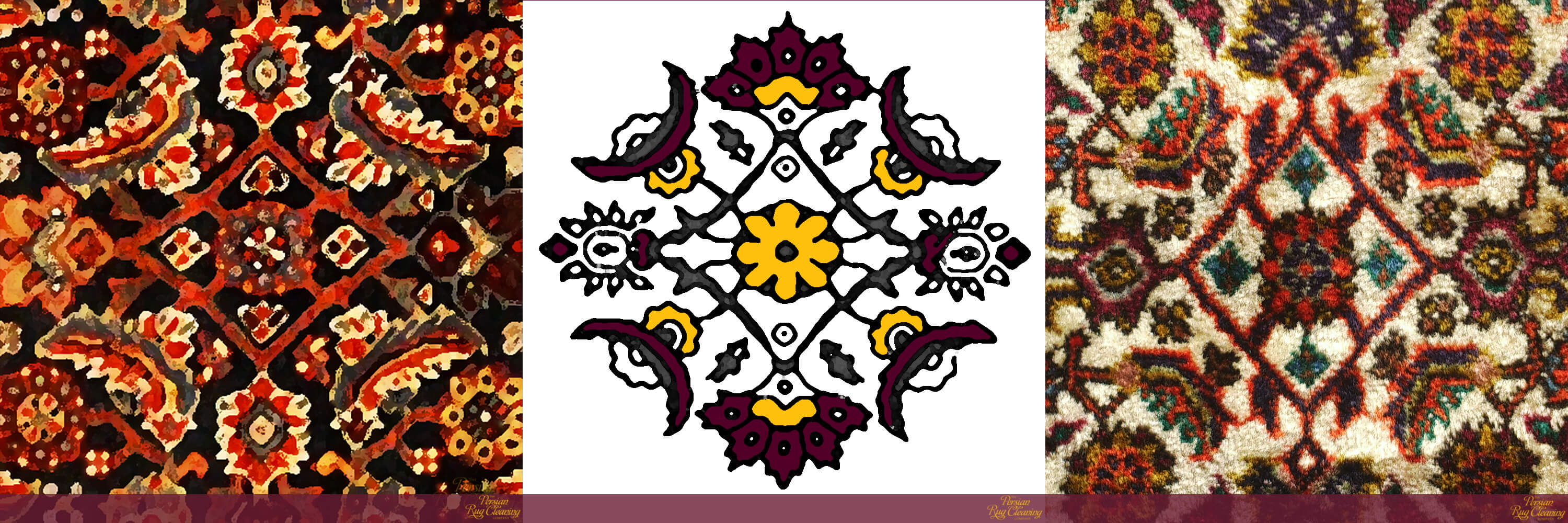

Herati – The Fish Motif

History

The Herati is arguably the most well known of all common rug motifs. It is named after Herat, an important town in the ancient region of Khorasan, now the capital of Herat province in Afghanistan. The town has always been a strategic trade route on the ancient silk road due to it’s convenient position as the gateway to Iran to the west and with Turkmenistan to the north. Many ancient empires have expanded their reach to take control of the town including the Mongols, Uzbeks and Saffavids. In the first half of the 15th century CE Shāhrukh, ruler of Mongol Timurid dynasty, actually chose Herat as capital of his empire and established a bustling trade community while also transforming the town into one of the greatest centres of art, cultural progress and learning in central Asia[1].

During the rule of Shah Ismail I, founder of the Safavid dynasty, Herat was capital of Khorassan province. Trade was the key to Herat’s wealth and so the promotion of the arts from the Timurid occupation was maintained by the Safavids. This led to the greatest era of carpet production in Persian history. Rugs from surrounding villages and towns, many of exemplary quality, were traded in Herat, fuelling a growing appetite from Europe where they earned an impressive reputation as weavings of fine quality with beautiful design. The Herati is one of these important designs which endures to this day.

Herati Design

The Herati motif consists of a floral rosette, enclosed centrally within a diamond flanked by an Acanthus leaf on each side. It is commonly known by it’s Farsi name ‘Mahi, meaning ‘fish’, after the appearance of these lanceolate shaped serrated leaves. Although the design thrived during the boom years of trade in Herat, the location of it’s conception is still open to debate. In fact, carpet scholars still have conflicting views about which came first, the geometric or the floral execution of the motif.

Herati motifs are usually found on Persian carpets in an allover pattern, and they are most commonly associated with carpets and rugs of Tabriz, Bijar, Senneh and, historically, Ferahan.

Mahi Tabriz

The classic mahi Tabriz is a good example of a rug that uses the all-over herati pattern. The shape and design of the motif in it’s modern floral adaptation used in Tabriz allows it to be used to create an organised web of uniformity and overall tidiness. Soft earthy tones are used in mahi Tabriz rugs. This creates a harmonious symphony of colour which complements the bold pattern. At first this can appear complex, but on closer inspection reveals it’s simplistic and seamless repetition. Fine Tabriz rugs, made with at least 300KPSI, allow the herati to be woven in this visually striking and balanced composition. These pleasant asthetics achieved by using the Herati motif have earned Tabriz it’s reputation as ‘The designer’s rug’.

Bijar

In rugs like the Bijar where the same allover mahi pattern is often executed with a far lower knot count, the visual allure and balance of the design is lost. The lack of detail can make the pattern look busy, muddled and confusing. In my opinion this lack of detail actually adds to the charm of the herati pattern on Bijar rugs. A sharper, more accurately executed motif is not necessarily more aesthetically pleasing.

Ferahan

Ferahan rugs, produced in the city of Arak, from the 19th and early 20th century CE, were famous for the all-over herati design and even gave their name to the pattern. The term ‘ferahan design’ is no longer used to describe the repeating Herati although the moniker can certainly be attributed to their frequent and successful excecution of the pattern in these rugs. In contrast to the uniform way the design is used in Tabriz rugs, Ferahans have a more spontaneous style which gives an overall look of naive charm much like the Bijar.

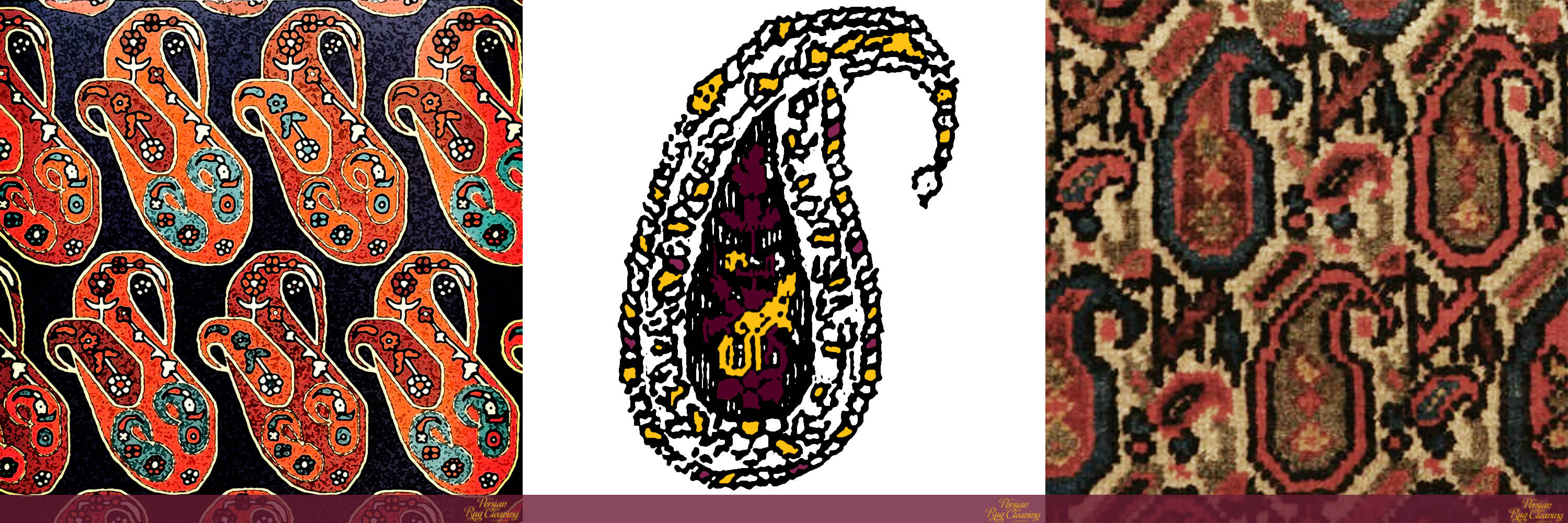

Boteh – The Most Adapted of all Common Rug Motifs?

Boteh Motif

Etymology & Interpretation

This motif named after the Persian word meaning ‘cluster of leaves’ or ‘bush’ is often referred to by English speakers as the ‘pear’ design due to it’s shape. It is also sometimes portrayed as a pine cone or fruit on a tree design and so ‘pine cone’ is also frequently used.

In Turkish weaving, the boteh is known as the ‘badem’ meaning ‘almond’.

Azerbaijani people call the motif ‘buta’. It is one of their national symbols, representing fire, used extensively throughout the country on garments, buildings and ornaments.

There is an interesting etymological relationship between the Farsi name ‘Boteh’ and the Hindi-Urdu term for the motif which is ‘Buta’. The literal translation for this Indian version is ‘Flower’, the motif being very important in Indian decorative art, gaining importance in the 17th century CE during Mughal reign[2]. As there is no early evidence of the design being used in India before this period it is possible that it was adopted from another source and interpreted as a flower rather than an animal or a fruit.

The rug historian P.R.J Ford states in his book Oriental Carpet Design

.. the origin of the motif can be traced to a plant form… (agreed) but if one were to ask a weaver in India – where the motif is widely used in carpet design – he might call it a ‘suggi’, which means a female parrot….because …the design resembles a parrot’s head and beak, or even a whole parrot”

The Scythians

The Scythians, an ancient Iranic tribe who occupied the central Eurasian Steppes between the 7th century BCE and the 4th century CE, frequently used animal designs in their artistry. Indeed the oldest known pile carpet in the world, the Pazyryk, which was found in a Scythian tomb in Siberia is adorned with aquine forms. Other ancient relics from this period clearly show mythical winged creatures such as griffins.

The Evil Eye

The so called ‘talisman theory’ takes myths and superstition one step further by suggesting that the common rug motifs we identify as the Boteh are in fact stylised from the ‘evil eye’, a symbol given great importance in Greek antiquity. The problem with this theory is that modern day Turks are perhaps the most staunch religious believers in the power of the evil eye yet none of their village rugs contain the Boteh. The same is true for the rugs and trappings of the Turkik speaking Turkmen tribes (with the exception of the Ersari Beshir) which are adorned with all manner of symbolic motifs of totemic purpose yet never include the Boteh.

The Boteh in Architecture and Clothing

Fire Temple

The earliest known use of the Boteh in architectural ornamentation can be seen in the column capital of the Masjid-i No Gumbad ruins in Balkh, Afghanistan which date to the 9th century CE. Various Islamic scholars from the 12th and 13th century CE suggest the ancient mosque was a Zaroastrian fire temple [3]. This could explain why the Boteh is also referred to as a ‘flame’ motif although there is no apparent direct link between this architectural utilisation of the motif and it’s use in carpet and rug design, for which there is no example of before the 18th century CE.

Silk Garments

Interestingly enough, the site of the earliest physical examples we have of Boteh design embellishment on a fabric is an area which is not exactly known for weaving rugs. Silk garments found in cemeteries in Akhmim, a town in Northern Egypt, date back to the 6th-8th century CE.

Egypt was under Byzantine (Hellenic Roman) rule for much of this period however it fell under Persian (Sassanian) control for approximately 10 years from 618 CE[4]. We can link the use of the Boteh design on the silk garment to the Sassanids by way of their most important emblem and royal symbol, the ‘Simorgh’ (also referred to as the ‘Senmurv’), which features a mythical winged animal figure with Boteh shaped wings. The image of the Simorgh is evidenced in the arts and literature of many ancient empires which have been influenced by Persian mythology and culture. The Turkik speaking tribes of central Asia also retain knowledge of the creature in their mythology.

Can We Trace The Origin?

Could the Boteh have become an emblem with different meanings and represantations to different people completely independent of cross border influence? Or will we one day be able to trace it’s evolution and transition from one empire, culture and religion to the next? Unfortunately, until new archaeological discoveries are made we will have to continue to speculate on the Boteh’s true origins and subsequent symbolism.

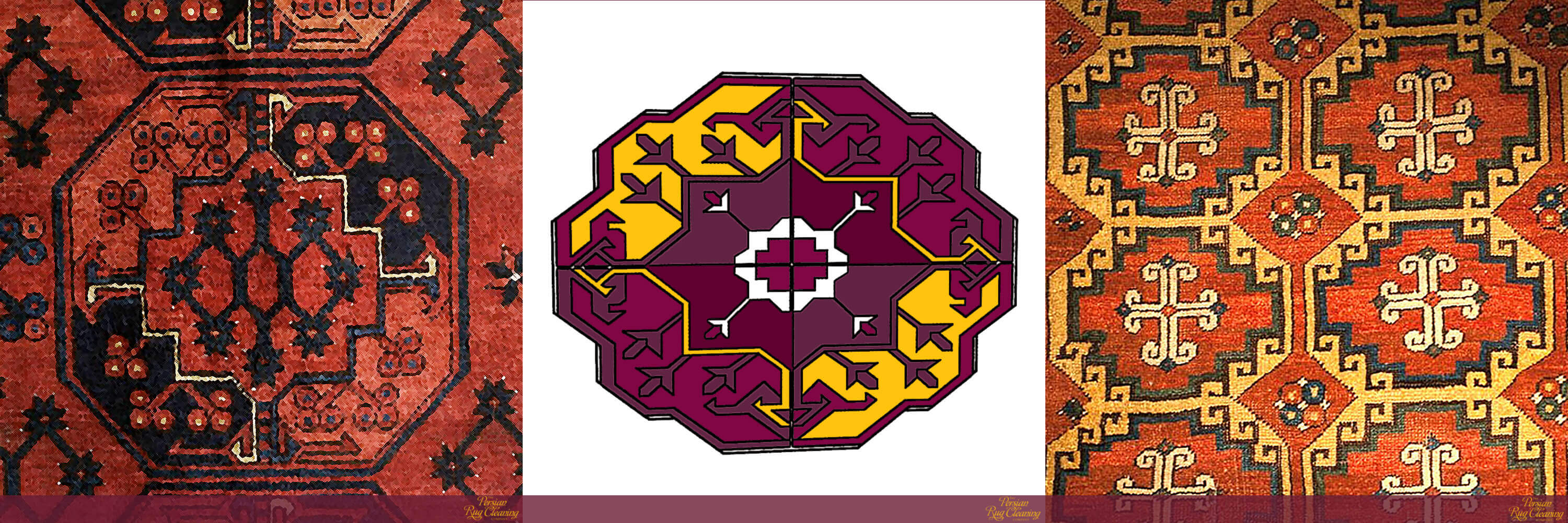

Gül – The Symmetrical Medallion

Gul Motif

The terms gol, göl, gul, or gül are loosely translated as flower or rose from the Persian word ‘gol’ or the Turkish ‘gül’. The spelling used is interchangeable amongst rug scholars in the west. The motif is executed as a symmetrical angular medallion in a repeating pattern, usually octagonal in shape, although it can also be hexagonal or rhomboid.

The Motif of the Turkmen Tribes

The gol motif is most associated with weavings of Central and Western Asia, especially those of the different Turkmen tribes. The gol used on a particular Turkmen rug or trapping can be used as a clue to identify the tribe that weaved it. The Turkmen have always used these gols as a sort of tribal coat of arms.

Tekke Main Carpet Gul

The gol used on the ‘main carpet’ of the Tekke tribe is a very well known and recognisable motif that appears to show multidirectional arrows in a symmetrical medallion, repeated throughout the field of the rug. We can confidently identify a Tekke main rug when we see this repeating motif (along with other features that help to distinguish it from Pakistani copies).

Gulli Gul

Another of the common rug motifs used by the Turkmen is the gulli-gul used predominantly by the Ersari tribe. The identifying design feature in this gul is the ‘tre-foil’ or clover leaf. There are many variations of this motif where different elements are combined with the tre-foil in an octagonal medallion. The tre-foil and star flower combination is a beautiful example of a popular gulli-gul used by the Ersari, and believed to be one of the oldest[5]. The tre-foil and memling gulli-gul is another interesting combination.

Tauk Noska Gul

Most of the design details used in Turkmen motifs can be interpreted as plant images however the Tauk Noska gul is most definitely animal inspired. It gets it’s name from the Turkik term meaning ‘chicken amulet’. The Tauk Noska may be the oldest gul used on the main carpets of the Chaudor tribe. It is also used by the Ersari and the Yomud tribes.

The Memling Gul

If you’re familiar with the works of Hans Memling, the 15th century painter, you may recognise the gul motif that was named after him. Many of his paintings feature Anatolian rugs with a field of repeating memling guls. Visually they can be described as medallions rimmed with stylised ‘hooks’.

Walter B. Denny, the American historian of Islamic art:

“..perhaps the most popular of all of the classical Anatolian rug motifs to have survived in Anatolian weaving”

Today, you can see the influence of this hook component in common rug motifs from virtually every weaving culture.

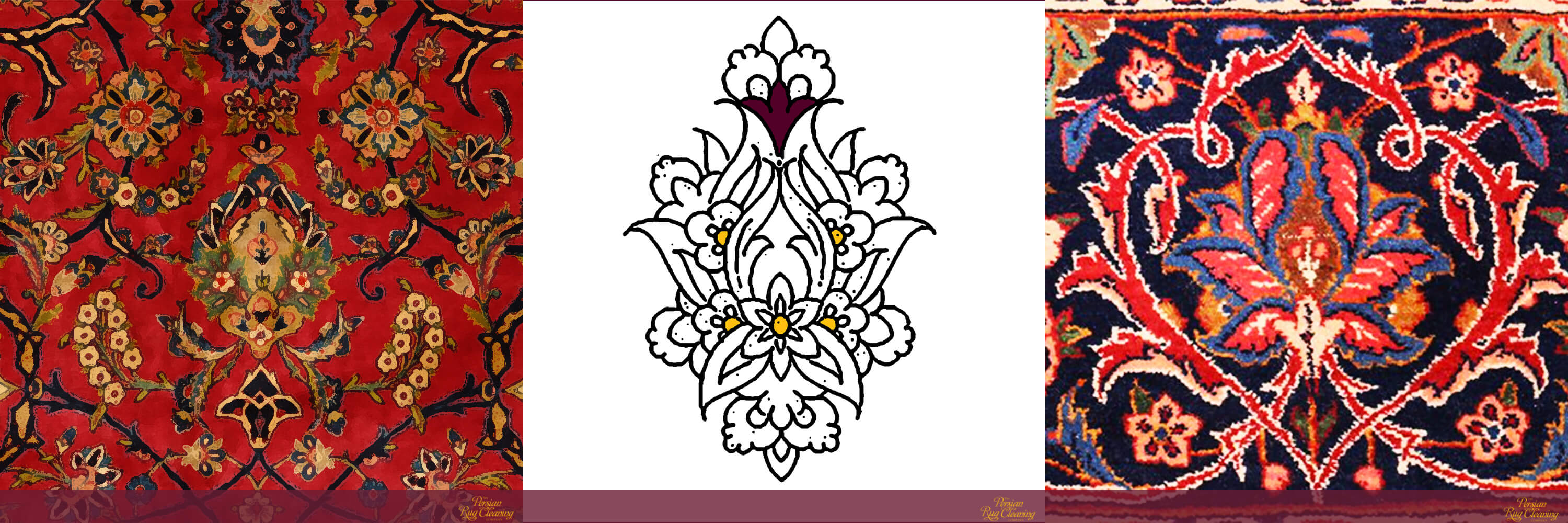

Mina Khani – The Floral Lattice Pattern

Mina Khani Motif

The rug scholar Peter Stone says of the the Mina Khani design

“The universal pattern derives from the Herati pattern of the 17th or 18th century”

The similarities are certainly evident when comparing the two patterns side by side. The mina khani design consists of an allover lattice pattern created with interconnected flowers. There are many variations of the pattern ranging from a classic curvilinear representation with a circular vine surrounding the main palmette flower, to a more geometric style where the lattice is more hexagonal, diamond shaped or even stepped.

Workshop rugs around the town of Varamin use the Mina Khani design so extensively that the design has adopted the moniker ‘varamin pattern’. Other weaving workshops in and around Tehran also make use of the design.

The mina khani is also one of the most common rug motifs used in the weavings of the Balouch and Luri tribes.

Shah Abbasi – The Stylised Flower

Shah Abbasi Motif

The Shah Abbasi design is composed of symmetrical stylised flowers called ‘palmettes’ which feature floral sprays. They are either interconnected in an allover pattern with arabesques or used in borders.

Due to the intricacy and detail of the palmette ornament this design is more suited to city rugs which can be executed in a higher knot count. Countries such as Pakistan, China and India which draw their influence from Persian rug designs also make use of the motif.

The Court Rug Era

The Safavid Dynasty

During the Safavid period of Persian rule, rug weaving became a display of artistic ability, status, and wealth. New techniques were developed and luxurious materials were employed in the making of ornately woven masterpieces, which distinguished them from the tribal and nomadic pieces from the past. Silk and gold thread was utilised to create mesmerising floral patterns. Curvilinear adaptations of geometric motifs and styles were developed to attain a level of mastery never before seen in rug weaving.

Shah Abbas I

The Shah Abbasi motif is named after the great ruler of the Safavid dynasty in 16th and 17th Century Persia, Shah Abbas I. He set up royal factories in major rug weaving cities such as Isfahan (the Safavid capital), Tabriz, Kerman and Kashan, under direct court supervision, to boost trade with Europe. Shah Abbas commissioned the most skilled weavers and designers in Persia. They produced spectacular court rugs in these factories with ever more intricate and detailed designs. Palmettes and arabesques were used in abundance. This was truly a new era in rug production; an era that showcased the Persian empire to the rest of the world.

Common Rug Motifs – Further Reading

Tribal and Village Rugs: The Definitive Guide to Design, Pattern and Motif: Peter F. Stone, Publisher: Thames & Hudson Ltd

Rugs of the Caucasus: Structure and Design: Peter F. Stone,Publisher: Greenleaf Co. 1984

Oriental Carpet Design: A Guide to Traditional Motifs, Patterns and Symbols: P.R.J Ford,Publisher: Thames & Hudson Ltd

Hello Nick,

Really enjoyed your rug motif summary. Very clear and concise, and excellent graphics as well.

I’m a rug collector (and sometimes seller) in the U.S.

I often try to explain the motifs to people inquiring about rugs, and now I can send them here.

Very interesting group of writers you recommended. I used to read a lot of novels but find myself reading mainly non-fiction these days — primarily science with some history and philosophy thrown in.

Thanks again.

Thank you for taking the time to read. I’m glad you enjoyed it!

Really great and informative article. I have several rugs and carpets left to me by my mother, which I love. I knew something about some of them but your article has helped me identify them. Thank you!